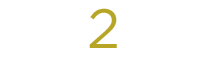

August 25-31 marks the annual Black Breastfeeding Week. The event was developed to encourage more Black mothers to breastfeed. It also seeks to counter the historical trauma and medical racism that has long kept many moms from nursing their children.

In its ninth year, the event offers a plethora of informational webinars, educational panel discussions, and even online socializing sessions for moms, those hoping to be one or anyone else who is interested in exploring the nuances of Black nursing.

The theme for this year’s BBW is “The Big Pause: Collective Rest for Collective Power.”

Organizers want to highlight the power of rest in Black women’s work and movement.

BBW was founded by three women who all have a special interest in seeing Black mothers who are nursing or have a desire to nurse– succeed. Kimberly Seales Allers is a journalist who focuses on increasing awareness of breastfeeding in vulnerable communities. Kiddada Green is the founding executive director of the Black Mothers’ Breastfeeding Association and focuses on training public health professionals on cultural competency. Anayah Sangodele-Ayoka is a writer and speaker on the topics of maternal health and breastfeeding. She is also the co-editor of Free to Breastfeed: Voices from Black Mothers.

Breast milk has long been considered the superior form of nutrition for all babies. Breastfed children have lower incidences of illnesses such as ear infections, digestive upset and respiratory infections. Further, breastfeeding offers a stronger defense against infant mortality.

Unfortunately, Black mothers are more likely to lose their babies to infant mortality to the tune of at least double the rate of white babies. Breastfeeding is also shown to decrease the incidence of disorders that African-American children are more often diagnosed with, such as asthma and diabetes.

As with all things centered on Black women, the question often arises about whether or not a need for a breastfeeding week specifically geared towards Black women is necessary.

The answer is a resounding, “Yes.”

Why? The short answer is racism.

In her 2017 poem “I Wish I Dried Up,” Hess Love summed it up perfectly.

“I wish I dried up.

I wish every drop of my milk slipped past those pink lips and nourished the ground.

Where the bones lay

Of my babies

Starved while I feed their murderer….”

Black women share a historical experience often filled with trauma that has often presented a barrier to breastfeeding their babies. Researchers have found that the “mammy” experience embedded in the genetic memory is a link between lower breastfeeding rates.

The slavery-era mother who was forced to nurse her white master’s children while her own cried in hunger still influences us today. Even after slavery, Black women worked in homes as domestics where they were tasked with nursing their employers’ children. Though the issue has been discussed for years among Black breastfeeding advocates, the broader community largely ignored it.

Wet nursing, as it was called after slavery, is a practice that is drenched in white supremacy, memories of slavery and medical experimentation. Breastfeeding enhances the bond between mother and baby, but that is hard when generational trauma mandated that the connection between Black women and their own children was second place.

Another barrier to Black mothers breastfeeding is racial bias in the healthcare system. A multi-authored study in the Journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics showed that Black babies were nine times more likely to be given formula in the hospital than the babies of white women.

This is a concern that Black mothers often face, even after they are discharged. Nzinga Jones, founder of the popular Black Breastfeeding Mamas Circle group on Facebook, noted that women are often given poor information on milk supply, and they turn to formula believing they have no other options.

“The biggest issue, by far, is perceived low supply. But we no longer have the communal knowledge about how breastmilk is made and how breastfeeding works, and so very often we see mamas panicked and supplementing when their supply is fine,” Jones said.

The need for evidence-based information is important. However, only 10 percent of the professionals in the lactation industry are Black. Under the tenets of medical racism, when the people who have the knowledge don’t recognize a patient’s personhood, beneficial information is often withheld from that patient.

Lastly, socioeconomic status disproportionately hurts Black mothers who are interested in nursing their children.

Although medical experts recommend that babies are breastfed exclusively for at least six months and continue through 12 months, the rates of breastfeeding decline according to the mother’s education and income level.

In households with adequate income, there is also usually more of a support system that will facilitate meeting nursing metrics such as longer maternity leave, pumping support, nannies and a culture that views breastfeeding as a high-status symbol.

Allers likens this to the food deserts common in underprivileged neighborhoods.

Despite the challenges, more Black women are embracing breastfeeding. Over the past nine years, grassroots organizations such as Black Breastfeeding Week have done the work that the medical and lactation industries have neglected.

Additionally, Black women have begun to explore the lactation industry thanks to women like Janiya Mitnaul Williams who is the program director of the Pathway 2 Human Lactation Training Program at North Carolina A&T State University, an HBCU. Her goal is to create better health outcomes for Black mothers through diversity in lactation education.

Black women have been in this country since at least 1619. For most of that time, they were forced to put themselves and their children last.

Black women breastfeeding their own children is truly a revolutionary act.